It’s 11:00 p.m. on a cool spring Friday night. A diverse crowd converges outside the Electric Brixton to attend a night of Yung Singh’s EKTA—his future record label and current brand of club events that are way more than just a ‘Punjabi night out’. A half hour goes by, and the crowd becomes antsy, wondering when they’ll be let in. What they don’t get to see is what’s happening on the inside. It took almost two hours to convert the previous night’s concert settings to the Ekta standard: last-minute stage setups, quick changes, lineup adjustments, sound checks, catch-ups with the lighting team, cleaning up—you name it. Yung runs across to each department to make sure everything is as close to perfect as possible for when the ever-growing line of music lovers gets let in, 50 minutes late, while a crowded group of artists are backstage, getting themselves photo-ready between three dressing rooms. Once we’re inside, DJ Kiran immediately turned it all around by playing an excellent opening set filled with UK Garage, House and other original blends with Punjabi vocals.

From the outside, Yung appears to be a perfectionist, not for any selfish reason that the average creative might have, but to ensure that the audience experience is the best he can provide. In between the fleeting moments that he allows himself to enjoy his night, he calmly stands in the corner, arms folded and assessing, ready to get hands-on with anything that might need his attention. As a globe-trotting DJ, he’s very accustomed to problem-solving when things go awry at the last minute. As a trailblazer in the brown creative community, he’s also hyperaware of wanting to create a safe and welcoming environment for discovering new music and Punjabi culture, considering that he’s also one of the very few South Asian musicians to have ever booked the venue in its 13-year history. The education and enlightenment go both ways on the night, not only to enrich British South Asians with aspects of their heritage they didn’t know but to also create allies in others that would never otherwise burst out in ‘Phul Punjab’ or ‘Pehlwani Dhamaal’ moves to Harmesh Meshi and Sukhshinder Shinda in the club.

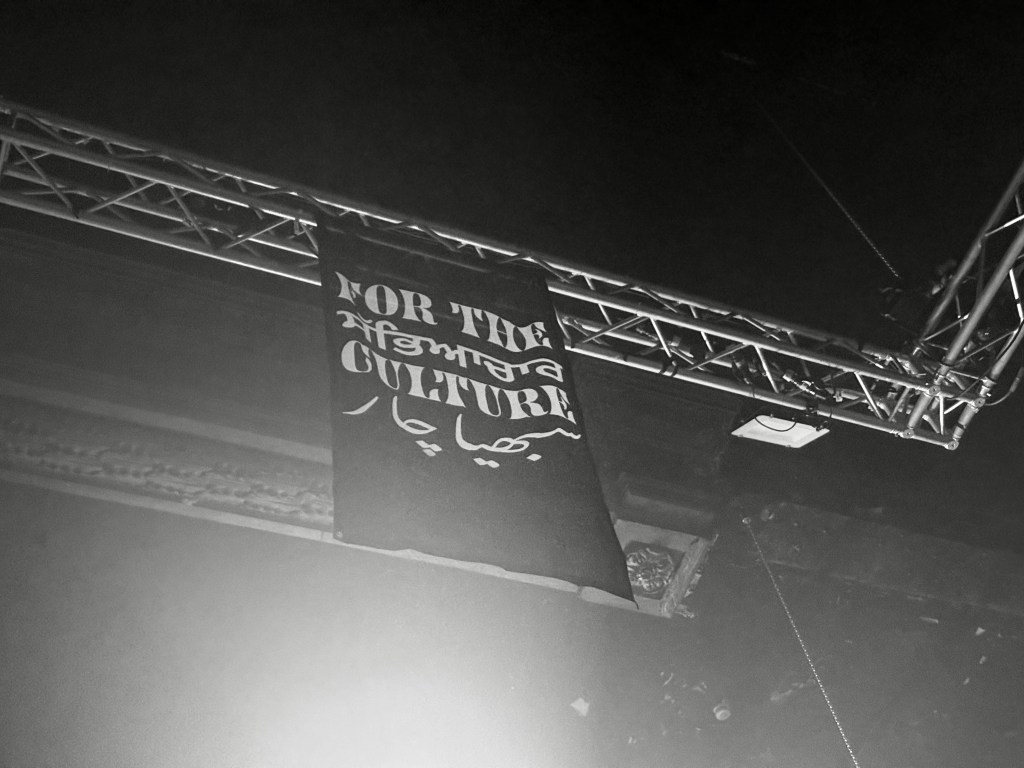

In March 2024, I attended the inaugural Ekta night, where Yung curated a three-room takeover at the renowned London nightclub, Fabric. The night was curated to perfection. There was a sound and a DJ that catered to everyone: Talvin Singh, a pioneer of the South Asian Underground, performed a live set blending tabla with drum and bass. Vedic Roots cranked dub sirens throughout their jammin’ vinyl-only reggae set, part of Jawani 4eva’s room. Dubstep legend Sukh Knight took to the decks after Yung and Mirza performed the most memorable b2b, in the same building that Shivum Sharma, Noudle, and Avs were making names for themselves. That first Ekta night embodied, fully, the Britain I grew up in and deeply identified with. It was a beautiful fusion of Black and brown musical cultures, with flags proudly waving ‘Kisaan Mazdoor Ekta Zindabaad’ and the words ‘For Our Culture’ written in English, Punjabi, and Urdu—enjoyed massively by a crowd that included those who had been part of the first South Asian daytime raves and those discovering the underground sound for the first time.

Fast forward a year later, Yung Singh presents a second series of Ekta across four cities: Birmingham, Manchester, London, and Bristol. If last year’s lineup was all about the past and the present, this year was all about the future: Tye Turner, Anj Kay, Baby J, Junglebandi, Florentino, Surusinghe, Sharandeep, DJ Kiran, Bianca Oblivion, Bubski, Sooyeon, and a special b2b with legendary UK Bass producer Champion. Not only is this roster of artists diverse in their taste in music but also in success. You have industry veterans being mentioned in the same breath as those on the verge of becoming the next big superstar DJs. For the majority of the nights I attended, I didn’t really hear Punjabi music. When I did, it was mostly laced with healthy doses of House, UK Garage, and Drum and Bass. These nights proved that it doesn’t take for it to be a ‘Punjabi night’ for you to be able to present your heritage in an authentic way. British culture is akin to worldly culture in the way we’ve taken so much from so many different people and their countries of origin; that’s why this crowd could comfortably dance to baile funk one second and bhangra the next. Ballroom-inspired House was effortlessly mashed up with Grime and the sounds of a tumbi. As crazy as that all sounds, it translates authentically. Every DJ who stepped onto the decks took us on a journey to explore global dance culture, in the way they experience it.

As meticulous as he is, Yung loves a bit of spontaneity. Before he jumps on the decks to headline his show in London, he introduces Junglebandi—a band he co-created last year that represents “everything from the land of the five rivers to the UK”, compiled of Dholi Vish, Vishal Mahay on tabla, and A.S. Kullar, who Yung called “one of the most talented producers in the Punjabi music scene”. For 30 minutes, they pair the digital sounds of House, Garage, Drum and Bass, and Jungle to the live acoustics of Indian classical drums, with hype specialist HMC on the mic, and kept the crowd jumping and cheering. They gave us one of the most memorable moments of the night with massive singalongs to both Dawn Penn’s reggae classic “You Don’t Love Me (No, No, No)”, as well as a jungle edit of Panjabi MC and Sarvjeet Kaur’s irresistible “Boliyan”—that you could go from one end to the other in a split second is the perfect way to describe an Ekta event, in a nutshell. Yung laughs as he throws the drummers a challenge: he hits play on a fast-paced track that leans heavily on the bols and padhant stylings of a traditional Indian classical performance. He stares and nods enthusiastically as Mahay matches the melody perfectly and signals for the dholi to join. In a night of wall-to-wall electronic music, a five-minute interlude of classical ecstasy captivated that audience potentially more so than anything else played that night.

It’s important to note that the DJs he shares his platform with are the network of peers he’s made along the way, both online and IRL, as well as the idols that he grew up admiring, who have now given him the ultimate co-sign. The guys taking photographs and recording camcorder footage are his supporters from day one. The people dancing extra hard behind him are the friends who travelled long distances across the country just to support him in his endeavours. The love he receives is the love he projects back into every corner of the club. His fans channel their raw, kinetic energy back towards him from the dancefloor, and it goes round and round. That’s probably why the crowd never lost momentum; the hype just kept building and building. As with any good night, at one point, the phones disappear and people just two-step their worries away. I saw people from outside the South Asian community dancing just as hard to Arjxn’s “Ni Main Nacha Nacha” edit as they did to Zero & Tempa T’s “Watch The Skank”.

There’s this famous quote by Dr Caroline Leaf, where she says that “Your purpose is not the thing you do. It is the thing that happens in others when you do what you do.” We are all living in the aftermath of the Yung Singh effect. The global spotlight he’s given to the Punjabi Sikh and South Asian identity has been incredible. What he’s done to highlight the South Asian underground scene has been immeasurable. He himself is a canon event for the culture, and he does it all with a smile on his face. Yung just wants people to have fun during his sets, but at the same time, he’s constantly building bridges to different audiences through a shared love of music and the way it makes us feel. His passion for creating spaces where identity and sound collide in refreshing ways, while educating us on his heritage and the real-life socio-political issues happening across the Punjabi diaspora on his social media, makes for a fascinating cult following based on unity, above all else. In a similar fashion to what Jyoty and Homegrown do, as well as what MTooray, Bianca Maieli, and No Nazar did, his personal brand of oneness and openness became the foundation of these nights, and this ethos is baked into the heart of Sikhism. Sikh Gurus emphasised unity among people, regardless of caste, creed, or background. Much like langar at a gurdwara, his Ekta nights aren’t targeted at a specific demographic; it’s always been for everybody. Beyond the religious upbringing Yung had, his culture taught him traditions of hospitality and collective celebrations. From the Sufi poetry of Bulleh Shah to the folk songs of Surinder Kaur, the music he grew up with often spoke about love, unity, and breaking barriers, and he lives out this purpose every day.

I got to interview him backstage about this second Ekta series, his British upbringing, and discovering more about his Punjabi Sikh heritage along his journey, as well as the prospects of new music.

Here’s what he had to say:

Let’s take a moment to reflect back on March 2024, when you launched the first EKTA series at Fabric with a three-room takeover. What do you remember about that night and what overall feedback do you remember getting from both the artists and the ravers?

Yung Singh: I was running around a lot, like we are right now! I remember meeting a lot of people, a lot of friends. I remember really enjoying my set—probably the most enjoyable set I ever had last year. It was good fun! The feedback was pretty good; I think the main criticism during my set was that a lot of people struggled to get into Room 1 [where Mirza and I played] but apart from that, it was all pretty good. A lot of people were stoked to see a full Punjabi lineup that covered electronic music completely. When I first suggested it to my team and a group of friends, they all said “are you sure?” Ha!

How did that experience shape your approach to curating this second series?

Yung Singh: I think it gave me a bit more confidence that the curation was on point. Especially the flags—I increased focus on the flags because people loved that stuff. I’ve been tagged in so many photos because of those flags. I honed in on those more intimate things that people would notice. I spent more money on flags, getting merchandise, that kinda stuff.

Tell us more about curating these nights: what qualities do you look for in a DJ before co-signing them for such a significant event? How do you ensure that the synergy between the artists on the lineup and the vibes of the night are just right?

Yung Singh: A lot of it is about having an intangible and holistic approach, in terms of the vibes. For example, Bianca Oblivion. I know she’s really interested in Punjabi culture but just culture in general. Me and her have had [many] conversations about the intersections of our different cultures. She was playing some Punjabi music and South Asian music in her set tonight. Same thing with Jarreau Vandal last year, when he played in Birmingham. But then also, Junglebandi—who I helped put together for Season 1 last year—would now gain new confidence and develop their live sets into something a bit more substantial, rather than some ‘two week, put together, 4am studio sessions’-type thing that we were doing last year. Baby J, who played in Birmingham, literally played her first set about 9 months to a year ago. She’s had an amazing rise and I caught her while she was in the UK. I took her and Tye [Turner], who runs Syber [event series in Perth where Baby J first caught attention] and tours with her, to Soho Tavern to get a mixy, you know what I mean?

It ultimately comes down to musical ability. I look for people that aren’t very genre-specific. I know a lot of Punjabi or South Asian people are gonna come to these nights and dig the global club sound. It’s just a bit more fun! Usually those kinds of DJs, similar to Jarreau Vandal, will dabble into Punjabi or South Asian stuff a little bit more after their sets. I love DJs that are more genre fluid. I don’t wanna just say ‘open format’ but I also love seeing their approach to culture and music [being] a bit more receptive.

What was the thought process behind keeping Manchester’s lineup so secretive this year?

Yung Singh: That’s because Amber’s don’t release their lineups on Saturdays! It’s also something that I’ve wanted to do [for a long time]. When I used to first go out when I was 18, it was, like, £5 tickets that you could buy on the door, you’d go in and have a good night out and it’s chill. You have low expectations with a £5 ticket because you don’t know who’s playing. We had Florentine in there, Surusinghe in there, Sharandeep playing and it was just really good, fun energy! We had a young, motivated crowd and it was low pressure. You’re paying a fiver for a ticket and you’ve just got an amazing, world class lineup. I think that kinda adds to the vibe as well, but yeah it was just club policy. There was nothing special about it but it fit into what I wanted to do, which was fantastic.

Sometimes, I think we take for granted that we have these kinds of events hosted by people that are so driven by the passion to create something of merit and, so, I want you to take the time to school us: How long does it typically take to create an EKTA event? What are some of the key factors you have to consider when planning something of this scale, and how many people are involved from ideation to completion?

Yung Singh: It probably took around six months? I think I submitted my first proposal in September/October last year and now we’re at the end of March. There’s always hiccups along the way. People will say yes, they’ll get an offer from someone else and it’s like triple the money, or people rearrange their tours and now they’re not in the country anymore. There’s so much stuff that happens behind the scenes and so many moving parts, so it takes a while. In terms of the team, it’s me, my agent and his assistant. That’s it. I’ve got friends helping out, obviously, but I organise everything, liaise with all the promoters and venues, whomever they might be. I was here from 9:30 p.m. – 10:00 p.m., putting up flags, helping them clean, and stuff.

Everything I do is like a one-man band and it’s intense but I’m so specific about what I wanna do, that, even if I was to hire more people, I wouldn’t ‘micromanage’ them but I’d have to have some input into what they do so I might as well do it myself! I’m very blessed to work with such an amazing support network—even last year, friends were driving me to places and helping me put up flags in Manchester, and it’s like, for them it’s just a fun night out but they’re also here to help me. You see those vibes onstage when they’re dancing up and down and they’re focused on the music. That helps as well.

The dance floor has always been a haven for so many people over the decades and I think this second wave of South Asian ravers are understanding that too. When was the first time you felt truly at home on the dance floor—whether as a raver or as a DJ?

Yung Singh: I don’t think I’ve ever not felt at home [on the dance floor]. I’ve always raved to Garage, Jungle, UK Funky, all that kinda stuff. I’ve never had a complex about being Punjabi. I’m very blessed to come from such a rich culture and I think it’s quite unique to the Punjabi diaspora that you grow up speaking Punjabi at home, eating Punjabi food and listening to Punjabi music, whereas there was a large portion of the South Asian diaspora that grew up kinda hating themselves and their cultures. Ironically, some of those people used to call us ‘freshies’ or ‘foji’s’ and stuff like that because they thought we were too ‘whatever’ for engaging with our culture. Now it’s all cool! It’s not a coincidence that a lot of that, maybe 90% of it has been led by Punjabi artists and DJs. You can extrapolate that to previous scenes as well. During the [birth of the] Asian Underground, Talvin Singh was the poster boy. Even during the original daytime scene in the ‘80s [and 90s]; you had Punjabi’s on both sides. It’s a very strong cultural identity. I grew up very British but I also grew up very Punjabi as well. I’m a proud Garage, UK Funky, Jungle lover. I’m also a proud Punjabi music lover. I’ve always found room on whatever dance floor I find myself in.

It’s a privilege to feel that way in this world but part of these events is promoting that unity, the oneness. I want people to feel that [because] it’s not always an easy thing to navigate. It’s tough being in the diaspora as a third culture kid; I’m still tryna figure that shit out. Everyone’s tryna figure that shit out. I’m hoping that this is the kinda space where we can platform Punjabi culture but not be pigeonholed by it. Platforming Punjabi talent but not have it only be us [and] having people who aren’t Punjabi or South Asian engage with the culture too. We have so many examples of it being utilised on a global scale [whether it’s our] music or food and everyone enjoys it so why don’t we do more of that? We don’t we share the culture? We’ll always get good music and great cultural output from that.

I want Ekta to be the intersection of so many different cultures and for people to be proud of their own cultures, whether you’re Punjabi, South Asian or you’re from wherever. I want other people to come through and say ‘this is cool’ and [then think that] Punjabi music’s cool, which would kinda be reflective of my artistic career.

The dance floor also stands as one of the only few incredible spaces left where we can express ourselves politically. How does it feel to look up from your decks and see flags waving that talk to political statements that you might align with?

Yung Singh: It’s all very cool! I creative directed and helped design those with my graphic designer and illustrator, Jaden Tsan. I even wrote the Ekta branding design brief for Jessie Sohpaul. I write very specific, detailed briefs; I’m super involved with everything. Not to take away from their talents, of course. There’s a reason why I’ve chosen to work with certain people to help me execute my vision but the vision is mine, the ideas are mine. The execution is all the graphic designers and illustrators I work with. All the phrases on these flags, I’ve done myself. I worked with people like my friend Samraj, who helps with Punjabi phrases and things, he’s just a mad linguist. It’s also inspirational for me as well because I’ve taught myself [how] to read and write in Punjabi. I never learned as a kid. I didn’t want that ‘For The Culture’ slogan to be just an empty slogan.

I put that into action [the best I can]. I have a lot of reading resources available on my website. I don’t wanna profit from the culture and not give back. I can’t put out T-shirts saying “for the culture” and then not do anything for my culture.

I can do other stuff as well, but there needs to be something a bit tangible, so that’s what the inspiration behind some of these flags is, and those political statements are calls to action as well.

How many years have you been DJing for now?

Yung Singh: About 9-10 years, give or take?

What continues to bring you joy in DJing after so many years in the game?

Yung Singh: There’s always new music, always new people, places and scenes to keep you on your toes. The feeling of a crowd going berserk and that sense of community on the dancefloor will never get old. Put it like this—does a striker ever get sick of scoring goals?

After such high-energy shows, how do you typically unwind and recharge?

Yung Singh: I hang out with my friends and family or I jump back into a good TV series or movie; trying to catch some footy highlights immediately after a show always helps! After that, I just try to make sure I get enough sleep, hit the gym and switch off from the online world as much as possible.

While I have you, I can’t not mention it. The Boiler Room in 2021, where you introduced DAYTIMERS to the world—it changed everything. Not only for yourself as an artist and for the collective but for the entire South Asian underground scene. Four long, busy, incredible years later, does it ever dawn on you the scale of impact you’ve made on our community?

Yung Singh: That had an incredibly big impact on me and it was truly a watershed moment but there’s still much more to be done. I just hope everyone else sees that long term vision!

Pivoting back to tonight, EKTA has been advertised as a future record label; why a record label and why now?

Yung Singh: My vision for Ekta, outside of a visual and physical experience is that it can also be a sonic one. The easiest route to have our Punjabi culture reach wider audiences is through music. It’s also motivation for me to get into the studio and learn this craft, rather than ‘just’ being a DJ. I don’t like having to rely on other people to send me tunes; it doesn’t always align with my vision, in terms of what I wanna hear and what I wanna do. It’s also just fun. Like, I’m a music nerd, right? I’m a nerd for, like, music history and culture. I’m a science nerd as well, so this career kind of incorporates all of that. I just feel like it makes a lot of sense to put out music that fits with that vision.

Last question, and we can use this as a platform to manifest: as a creative, I know you must have aspirations of doing and being part of things beyond what you’ve already achieved, a record label probably having been one of these things already. If anything were possible, what are some things you would hope to accomplish in the next 5, 10, 15 years time?

Yung Singh: Have Punjabi culture be culturally appropriated in the mainstream. Because when your culture is being culturally appropriated, that’s when you hit a much wider audience.

It wouldn’t be long before I’d see Yung again. A short two and a half months after his Brixton show, following an extensive spring tour season in Australia, New Zealand and Asia, he returns to the UK for the start of festival season. Two weeks before his fourth Glastonbury appearance, he’s scheduled to play at Ambassy—an intimate, after-hours party space found on the Lower Ground Floor of the Ambassadors Clubhouse—a fine dining restaurant, tucked away in a quiet corner of Mayfair, that celebrates Punjabi cuisine and culture. With a capacity of 120 people, suffice it to say it sold out. When I caught up with him at the end of the night, he was quietly buzzing; not with the adrenaline of a massive crowd like Glasto, but with the warmth of something far rarer. “I don’t get to play small venues like this”, he said. “This is maybe a once-a-year thing.” He takes a quick scan of the room and smiles to himself, “This was pretty special, hey!” He played a fun and unique set filled predominantly with Panjabi music from Malkit Singh, old-school Diljit Dosanjh, JK, and Baljit Malwa, mixed with some Beenie Man, Vybz Kartel, Crazy Cousinz, as well as some unreleased original productions.

While the room saw a mostly upper-middle-class South Asian crowd, dressed in smart casual, fill the dance floor and sing-scream the night away, as usual, his friends weren’t too far away. They stayed just off to the right of the decks and continued to bring life to the party from that corner. After all, the first thing you usually do after returning from abroad is spend time with family, right? With friends like DJ and radio presenter Ramnik Tatla on the decks as his opener, as well as Ambassy’s event programmer and Yung’s personal hype man Sukh Sohal waving gun fingers behind him, it definitely felt like a family reunion. No matter what corner of the world he finds himself in or what music he plays, a Yung Singh set is a masterclass in controlled chaos—it’s a frenzy from the decks to the dance floor.