Growing up a second-generation British South Asian, there are only so many pieces of Indian history that are inherently rooted within you over time: a vague understanding of the Mughal Empire, stories of colonialism and the British Raj, Mahatma Gandhi and his fight for Independence, Indira Gandhi’s assassination and the subsequent 1984 anti-Sikh riots and so on. You hear horror stories of Partition, the hurried expulsion of Ugandan Asians and the struggles of our elders assimilating into British society, against heavy resistance. Yet, one of the biggest and more recent political challenges in the country’s existence was rarely spoken of, nor prominently documented in Indian films that would make it to cinemas overseas. In 1975, India declared a state of emergency and suspended democracy in response to ‘internal disturbances’ that referred to labour strikes, mass protesting and disorder across country and political parties, to mention a few and as a result, fundamental citizen rights were curtailed and the press were censored and thrown in jail for speaking out against the authorities. In 1998, it developed nuclear weapons, to become an “emerging great power”, despite widespread denunciation from international communities. The 23 years in between were decades of pandemonium, which, inside this world-first exhibition, we’re invited to experience how good of a job the art created during that period tries to address.

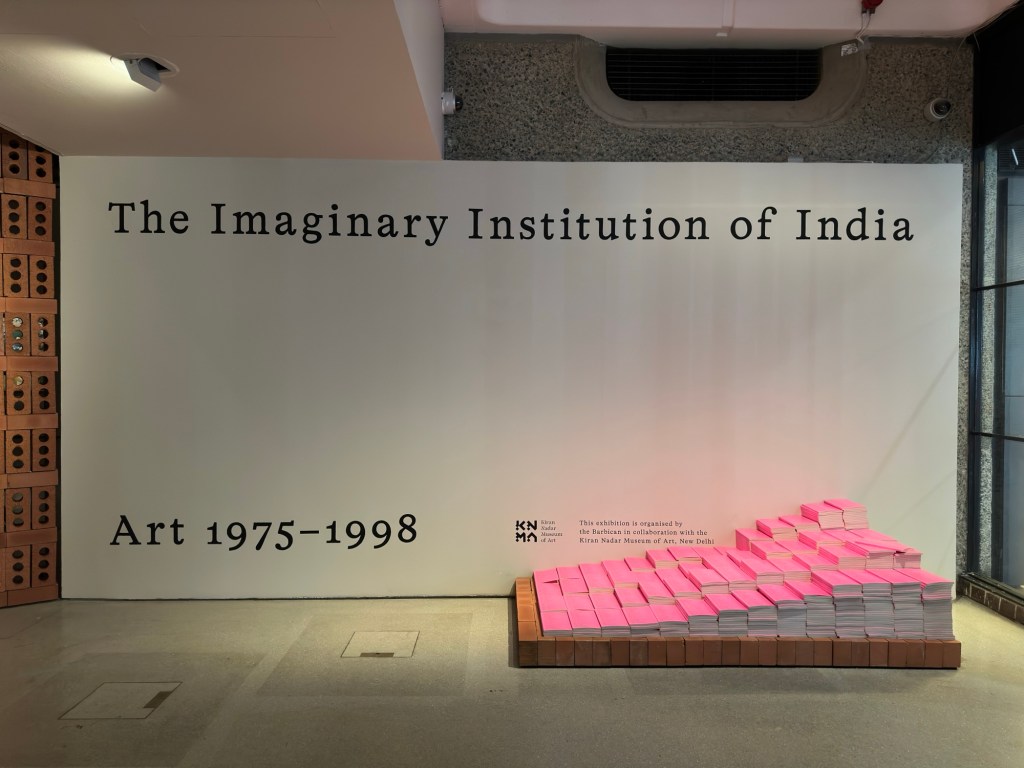

‘The Imaginary Institution of India’ is a landmark group exhibition, featuring over 30 artists, that explores India’s complex political story from three important decades, through the lens of sculpture, paintings, photography, installation and film. It is, in the best sense, a mishmash of multimedia, in a somewhat overwhelming display of tragedy, struggle and social change. At a glance, it feels like none of the works are convincingly or chronologically connected but mapping out the intimate ways in which over two decades’ worth of political unrest have affected the most populated country in the world is a big task. Upon entry, you’re given a pink guidebook to lead your way through the maze of works collated by the Barbican Art Gallery. It also serves as a historical guide for the periods the exhibition covers, featuring timelines of political events from 1975 to 1998, along with a glossary of Indian terms at the end. For a change, there is no written description on the walls next to the artwork. You stand there in front of a total of 150 pieces of art, spread across two floors, accompanied by short essays on the artists and their creations in your pink book. You read, you look up in wonder, you read again and you look up again, marvelled at what it all means in its wider context.

Some of these works are mounted very beautifully on freestanding walls of stacked, jaali-style perforated bricks. The crumbling, terracotta-coloured texture of these bricks brings you closer to the rustic worlds of the smaller villages and cities where the violence of the Emergency ran rampant, as Sanjay Gandhi’s campaign of mass sterilisation subjected more than six million men to forced procedures, torture and mutilations in a year.

Gulammohammed Sheikh’s ‘Speechless City’ paints a haunting image of a desolate urban landscape in the aftermath of Hindu-Muslim riots in Gujarat, circa 1969, while Bhupen Khakhar’s thought-provoking ‘Two Men in Benares’ blurs the boundaries around submission, whether holy and religious or provocative and sexual and if it should be public or private. Navjot Altaf’s black ink protest posters of fists and mobs are vexed, punk and raw—a stark contrast to Pablo Bartholomew and Sunil Gupta’s photographs, which depict the softer touches of everyday life, showing people trying to live and love through the times, in small parties, family gatherings and out in public, next to country landmarks. You’ll also see broken clay pots, collage work and an incredible, multi-channel video triptych from one of India’s first true video artists, Nalini Malini (her daughter Payal Kapadia carries the creative torch with her 2024 Cannes Film Festival fixture, ‘All We Imagine is Light’). You have such varying methods of expression standing next to each other, interweaving their individual stories to create a deeply cohesive understanding of how the people of India live through constant trying times.

Cutting to the chase, it’s a great show with some amazing pieces in it that will make you look at India from a different lens, especially from a diaspora perspective. There’s an incredible urgency conveyed through these many mediums, in the way these works describe friendship, love, family, religion, violence, community and protest—all in the face of unprecedented change. The gift shop ain’t bad too. It’s stacked with amazing cookbooks, children’s story books and other literature, kitchenware, home candles and a litter of other gifts and goodies from small businesses that promote Indian culture throughout their products.

If this kind of art history interests you in the slightest, get down to the Barbican Centre before the exhibition ends on Sunday, January 5, 2025.